By William A. Dembski (Author’s note: I’d like to thank my good friend James Barham, General Editor of TBS, for inviting me to contribute this article.)

Career or Calling?

You may not think of yourself as politically correct or politically incorrect, but ask yourself these questions: Do you feel passionate about some issue? Do you think that people on the other side of that issue are not just wrong but also doing the world harm? Is this a controversy that you just can’t let go? If so, you may have a future in a politically correct or politically incorrect career.

For most people, a career is two things: (1) a good job that pays the bills and leaves something extra for leisure; (2) meaningful work that is satisfying and enhances one’s identity. Yet for some a career goes well beyond that. For them it is a calling or mission to serve, and even save, humanity. A career thus becomes part of a grand effort to benefit the world and defeat evil.

People who take this approach to their careers are often criticized as zealots, fanatics, extremists, fundamentalists, militants, etc. Some deserve these labels because they use violence and other forms of coercion to advance their cause. Yet many “earnest advocates,” as we might call them, are committed to rational discourse. For them, reason (especially its ability to persuade a majority) rather than force is the preferred means to advance their cause.

To illustrate the difference between earnest advocates and extremists, contrast the civil rights movement of the 1960s with the Islamic Jihadists of today. The Islamic Jihadists attempt by threat and violence to transform Western culture, replacing it with a theocracy. The American civil rights movement of the 1960s, by contrast, overturned discrimination against African Americans by confronting repression with truth and moral determination, spotlighting the hypocrisy of a political system that promised equality to all but reserved it only for some.

Earnest advocates see their careers as part of a cultural conflict in

which they are on the right side of history, fighting against evil and

making the world a better place. Earnest advocates may be right (as were

the civil rights leaders of the 1960s) or they may be wrong. In fact,

the various factions in a cultural conflict can all be wrong. To the

question Which faction should I join?, the best answer may be “none of

the above.”

Key Cultural Conflicts

Cultural conflicts play out on the national stage in issue after issue:

- Gun control vs. Second Amendment rights

- Pro-choice vs. Pro-life

- Freedom from religion vs. Freedom of religion

- Animal rights vs. People’s rights over animals

- Vaccines unrelated to autism vs. Vaccines causally implicated in autism

- People’s right to privacy vs. Government’s right to spy

- Government controlled economics vs. Free market economics

- Global warming as real problem vs. Global warming as alarmism

- Evolution vs. Intelligent design / Creationism

- Legalize marijuana vs. Keep marijuana illegal

- Anti-capital punishment vs. Pro-capital punishment

- Expanded view of marriage vs. Traditional marriage

This list, though not exhaustive, is representative of the conflicts

beleaguering our culture and of the politically correct and incorrect

careers that these conflicts make possible.

The Two Poles in a Cultural Conflict

Cultural conflicts typically elicit a polarization in which two extremes, or poles, vie with one another. The role of these poles, however, tends be asymmetrical: one side typically has a cultural advantage over another.

A “cultural advantage” here means that government, media, and education favor one side rather than the other on an issue. This is not to say that government, media, and education have achieved unanimity on an issue, but they regard one side in a cultural conflict as “politically correct” and the other as “politically incorrect.”

In the list above, the politically correct side is listed first, the politically incorrect side second. Which is which is a judgment call, and changes as culture changes. Back up a few years and traditional marriage would have been politically correct; nowadays an extended view of marriage is politically correct.

If you want a career based on a cultural conflict, the safer course is to align yourself with the politically correct side. Usually that’s where you’ll find a larger community of support as well as more money (and thus more jobs) to engage in the cultural conflict. But it’s also where people have more to lose if the conflict turns against them.

Fighting on the politically incorrect side, however, has its advantages. In that case, you’re the underdog and it’s often easier to galvanize grassroots support. Consider, for instance, the underdog appeal of the following “Tea Party” advocate before Congress:

What is politically correct during one period can become politically

incorrect at a later time. Which is which depends on who holds cultural

authority and how cultural sensitivities change. For instance, before

the civil rights movement, racial discrimination was politically

correct; now it is politically incorrect.

What Do Politically (In)Correct Careers Look Like?

Politically correct and politically incorrect careers can on the surface look no different from many ordinary careers. Cultural conflicts require workers, and this includes everything from basic service workers (secretaries, maintenance people, office managers, etc.) to high-end knowledge workers (people with expertise related to the main issues of a particular cultural conflict). Nonetheless, politically (in)correct careers follow certain general patterns, irrespective of the particular conflict to which they are attached.

Because politically (in)correct careers are conflict based, attorneys and other legal workers tend to be disproportionately represented in them. Politically (in)correct careers are often pursued within non-profit organizations, which can be overtly activist (such as Planned Parenthood, which lobbies politically and also operates clinics) or more idea driven (such as the Ludwig von Mises Institute, which is a think-tank advocating free-market economics).

The academy is also a great place to pursue a politically correct career (less so a politically incorrect career, which academics tend to view with suspicion). For all its talk about diversity of ideas and freedom of expression, the American college and university system is remarkably homogeneous. Opinion polls of its members indicate a uniformity of thought on issue after controversial issue.

Thus, on the politically correct side of the dozen cultural conflicts listed above, academic positions exist to promote that side. This is especially true in the social sciences and law schools, but also in the natural sciences relevant to certain controversies (e.g., global warming and biological evolution).

Even though the academy tends to be much more friendly to the politically correct side of a cultural conflict, it is not exclusively so. Break-away institutions of higher learning exist for at least some of the cultural conflicts mentioned above. For instance, Grove City College and George Mason University are both centers for free-market economics. Moreover, the engineering school at Baylor University shows increasing friendliness to intelligent design.

What, then, should you do if you want to pursue a politically (in)correct career? A lot depends on your interests, talents, and ambitions. Are you content to play a supporting role? Cultural conflicts require many supporting services, such as managing an office or overseeing a website (and making sure it is not hacked — websites associated with cultural conflicts are at greater risk in this regard).

On the other hand, if you want to be one of the high-end knowledge workers in a cultural conflict, you’ll need the relevant education and credentials. Credentials are especially important if you are on the politically incorrect side of a conflict because without them, those on the politically correct side will dismiss you out of hand as someone who doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Just what education and credentials will you need to be a high-end

knowledge worker in a cultural conflict? It depends on the cultural

conflict. For instance, if your concern is global warming, the best way

to speak with authority on this topic is to hold a doctorate in

environmental sciences. On the other hand, if your concern is religious

freedom (especially the role of religion in the public square), then

having a law degree or a doctorate in political/social science is the

way to go.

The Arms Race

One advantage of a politically (in)correct career is that the underlying cultural conflict tends to have an obsessive vitality. This means that the conflict is likely to outlast your lifetime and provide you with long-term employment. This may sound cynical, but it is a reality about cultural conflicts worth bearing in mind.

Emotions in cultural conflicts run high. As a consequence, the temptation exists to demonize those on the other side. This is ugly when it happens, but from a career perspective, it has an upside. It keeps people passionate and contributing to the cause (after all, if demons are running the show on the other side, they need to be exorcised).

As noted earlier, many cultural conflicts are essentially run through special-interest non-profit organizations. Organizations dedicated to opposite sides of a cultural conflict thus square off against each other. This can lead to an arms race in which one organization denounces the other, emphasizing the bad things it is doing, and then appeals to its constituency for support in opposing the other organization.

As the one organization grows stronger because of increased support for opposing the other organization, the other organization can now appeal to its constituency for more support so that it can stand up to the first organization. Round and round it goes, with increasing support for both sides. Hence the arms race.

In these situations, a worthy adversary helps to advance one’s cause

and career. Again, cynical as this may sound, it is a reality. As the

saying goes, it takes two to tango. Politically correct careers depend

on politically incorrect careers, and vice versa. For a cultural

conflict to be worth our attention, the parties to it need to be heavily

armed and mean to do each other harm. Fortunately for politically

(in)correct careers, America has more than enough of these conflicts to

go around.

What to Do Now?

The previous discussion relating cultural conflicts to education, credentialing, and arms races may seem abstract. If you feel really passionate about a cultural conflict, what should you do right now, especially if you’re young and still have a lot to learn? A website like TheBestSchools.org can help you to sort through career options. But given your passion, you don’t want a career that’s only tangentially connected to the conflict; you want a career that will enable you to make the biggest impact in advancing your cause.

To choose such a maximal-impact career, you’ll need a mentor as well

as a community to guide and nurture you, especially if you are on the

politically incorrect side of a cultural conflict. Therefore, instead of

referring you to our other career articles, we are going to give you

the names of organizations with the people and resources to guide you in

pursuing the politically (in)correct careers associated with the twelve

cultural conflicts listed earlier.

(1) Gun control vs. Second Amendment rights

The gun control debate hinges on what to do with the Second Amendment. The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution reads, in its entirety: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

One view is that the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” is an individual right. The other view is that the first clause qualifies this right, restricting it to a well regulated militia. Furthermore, it is argued that “a well regulated militia” is under state control. Accordingly, local, state, and federal legislative bodies have authority to regulate firearms.

“Anti-gun” groups:

- Brady Campaign

- Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

- Mayors Against Illegal Guns

- States United to Prevent Gun Violence

- Violence Policy Center

- Third Way (formerly Americans for Gun Safety)

“Pro-Gun” groups:

- National Rifle Association

- Women Against Gun Control

- Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms

- Firearms & Liberty

- Gun Owners of America

- Second Amendment Foundation

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(2) Pro-choice vs. Pro-life

Pro-choice refers to the position that there is nothing morally wrong with abortion, at least in the first trimester or two of pregnancy. Thus, the choice of whether to seek an abortion has no bearing on society as a whole, and ought to be left entirely up to the individual woman. Typically, pro-choice advocates view the developing fetus as essentially different from a newborn infant, which means that the normal prohibitions against killing do not apply to it.

Pro-life refers to the position that abortion is morally wrong under most circumstances (perhaps with some exceptions, such as rape and incest, or to save the life of the mother). Typically, pro-life advocates view the developing fetus as not significantly different from a newborn infant, which means that the normal prohibitions against killing do apply to it.

Thus, the disagreement between the two sides is ultimately about the identity of the fetus. Is the fetus fully human, with all the rights that properly belong to humanity, or not? By answering no to this question, pro-choice advocates conclude that no one can legitimately maintain that killing fetuses is morally wrong, and therefore society ought not to prevent it—a woman ought to have the right to decide whether to abort for herself. On this view, denying her that right is a form of political oppression.

On the assumption that the fetus is fully human and deserves all protections and privileges properly accorded to humanity, pro-life advocates reach a very different conclusion: killing fetuses is obviously wrong. Morally revolted by graphic depictions of late-term abortions, they see in abortion a slaughter of innocent human life. On this view, no woman can rightly bring herself to abort her fetus.

Pro-choice groups:

Pro-life groups:

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(3) Freedom from religion vs. Freedom of religion

We live in a pluralistic society. Freedom of religion is guaranteed by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, the relevant portion of which reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

But what, exactly, does the phrase “freedom of religion” mean? No one disputes that the U.S. ought not to have an officially established, or government-sanctioned, religion. However, some people interpret this principle (also known as the “separation of church and state”) in a broad way, to mean merely that no one religion ought to dominate in the public sphere.

Others interpret the principle much more strictly, to mean that government officials must refrain from any and all expression of religious belief or feeling—that religion must be banished from the public arena altogether.

Let us call the first position, which is the traditional position that has been understood by the majority of jurists and ordinary citizens from the founding of the nation until recently, the “freedom of religion” position. The other position, then, may be termed the “freedom from religion” position.

The freedom-from-religion advocate believes that fellow citizens who are religious believers may rightly be required to keep silent about their beliefs while working in any sort of official capacity. The freedom-from-religion advocate claims a right not to be confronted with other people’s religious beliefs whenever venturing into the public sphere, or engaged in any sort of official business. Fellow citizens are to keep their beliefs to themselves, and express them only in the privacy of their own homes or in other private places.

The freedom-of-religion advocate, on the other hand, believes the freedom-from-religion advocate’s demands are unreasonable. To be sure, no one particular religion may be established as the official religion in the U.S.—both sides agree on that. But why does that mean that the religious believer must renounce the right to express one’s beliefs openly if he or she happens to work in the public sector? The freedom-from-religion advocate may find religious expression distasteful, but that in itself does not give him or her a right not to be exposed to it.

In sum, the freedom-from-religion advocate sees any expression of religious opinion by an individual public official, or group of public officials, as tantamount to a forbidden “establishment of religion,” whereas the freedom-of-religion advocate sees expressions of religious opinion by individual public officials, or groups of public officials, as just that—merely expressions of the opinions of those individuals or those groups.

Freedom-from-religion advocates:

- American Civil Liberties Union (or ACLU)

- Americans United for Separation of Church and State

- Freedom from Religion Foundation

- American Atheists

- Atheist Alliance International

- Council for Secular Humanism

Freedom-of-religion advocates:

- American Center for Law and Justice (or ACLJ)

- Alliance Defending Freedom

- Thomas More Law Center

- Manhattan Declaration

- U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops

- Acton Institute

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(4) Animal rights vs. People’s rights over animals

Human beings are omnivores. Humans are therefore meat-eating creatures. In all times and all places, until very recently, humans saw themselves as free to use the other animals for food.

However, we are also moral beings. The question is: What moral claims do animals have on us (what rights do they have)? Or, more precisely, what moral claim do some animals have on us (hardly anyone wishes to accord rights to cockroaches)? So, which animals, specifically, have rights? And for what reasons?

Those who believe that at least some animals have moral rights that human beings are bound to respect let us call “animal rights advocates.” Those who deny this claim let us call “human dominion advocates.”

As a matter of practice, animal rights advocates press their claims on behalf of the animals most like us—the mammals, especially the primates, the cetaceans (dolphins and whales), and domesticated species. But justifying this practice cannot simply be that those animals are similar to us in form (dolphins look very different from us and inhabit a very different environment). Nor can it be that they are closely related to us in evolutionary terms (dolphins are only distantly related to us). The reason must be, rather, that in their range of emotional responses, and in the sophistication of their behavior, they seem to be akin to us in intelligence and inner experience.

We must be careful to distinguish the debate between animal rights advocates and human dominion advocates from the superficially similar issue of the humane treatment of animals. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham pointed out long ago that some animals have a moral claim on us to be treated humanely, not because they are intelligent, but because they can feel and suffer. Some philosophers have denied that animals feel anything, but no morally sound person would inflict pain on an animal for no good reason. The question with respect to humane treatment is how much pain we are entitled to inflict, and for what purposes.

Nevertheless, the debate between the animal rights advocate and the human dominion advocate goes a crucial step further than the question about the humane treatment of animals. Even if all provision were made for treating animals as humanely as possible—that is, for minimizing the pain we inflict upon them as we use them for our various purposes—there would still be the further question of whether we have any right to use them for our purposes at all.

The animal rights advocate believes that, at least in the case of intelligent animals that give evidence of an emotional life, we have no such right. All consumption of meat ought to stop. All animal experimentation ought to stop. The reason is that we share a common nature with the higher animals—our common intelligence—and therefore, we ought to extend to the higher animals the prohibition against treating other human beings (persons) as only means to our ends.

The human dominion advocate, by contrast, believes the analogy between human and animal intelligence is defective. While we of course have a moral duty to inflict as little pain as possible, we have no duty to respect the “rights” of even the most intelligent animals, for the simple reason that only a human being is entitled to rights. Only persons are entitled to be treated as ends in themselves, and not only as means to others’ ends. And only human beings are persons.

According to this argument, animals cannot be persons, because their type of intelligence falls far short of human rationality. Only human beings have the gift of reason—here, the capacity to act and to refrain from acting on the basis of higher reasons that may conflict with immediate desires—and so only human beings can be persons entitled to rights. Human dominion over the animals is based on the fundamental difference in kind between rational creatures and merely intelligent ones.

Not being rational, animals cannot be held morally responsible for their actions (it would be absurd to put a chimpanzee on trial for killing a human being). By the same token, even the most intelligent animals have no rights we are morally bound to respect. So concludes the human dominion advocate.

Animal rights advocates:

Human dominion advocates:

- Center for Human Exceptionalism

- Tibor Machan (author of Putting Humans First)

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(5) Vaccines unrelated to autism vs. Vaccines causally implicated in autism

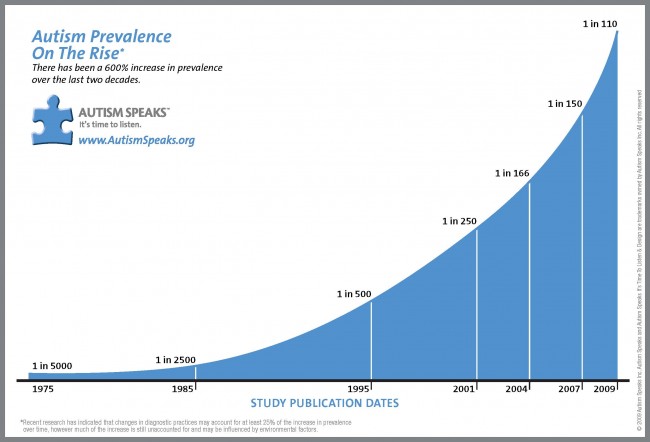

Autism rates have skyrocketed in the last 40 years. In 1975, autism afflicted 1 in a few thousand young people. By 2009 it had reached 1 in 110. Today, in 2014, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) puts the prevalence at 1 in 88 children.

This many-fold increase prevalence of autism over the last 40 years represents a staggering health challenge to the United States. The following jaw-dropping graph underscores the rapidly accelerating rate of autism (though the 1 in 5,000 figure in 1975 may be a bit extreme—other studies place it at 1 in 2,000):

Is this increase real? Could it be that doctors are now calling autism what previously they called mental retardation and other disorders? Is it just that medical professionals are applying the autism label to lots of cases that previously would have had different diagnoses, perhaps doing so because the money is in autism treatment and research?

While it may be that before 1980 autism was underdiagnosed, it’s certainly the case that in the last 25 years autism spectrum disorder has been clearly identifiable. The handbook for diagnosing mental health problems, known as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), is updated every now and again. The first edition of DSM IV, published in 1994, clearly delineated the criteria for diagnosing autism.

But what causes autism, and what is responsible for its rapid rise? Here the medical community admits ignorance. “Frustratingly little is understood about the causal mechanisms underlying this complex disorder,” write Craig Newschaffer, Lisa Croen, et al. in “The Epidemiology of Autism Spectrum Disorders.” To this Kathleen Doheny adds that the rise in autism rates is a mystery.

Clearly, with so rapid a rise in the disorder, some environmental factor or factors have to be playing a role. Vaccines have been charged with at least some of the increase in the autism rate. Others, who see vaccines as an overwhelming health benefit, resist this charge. The passions on both sides are intense.

People/groups arguing vaccines unrelated to autism:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Quackwatch

- American Pharmacists Association

- Autism Science Foundation

People/groups arguing Vaccines play a causal role in autism:

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(6) Government’s right to spy vs. People’s right to privacy

Which attitude should prevail: Innocent until proven guilty, or If you have nothing to hide, you shouldn’t mind us looking? The government’s growing right (or “need”) to spy is allegedly based on the idea that in order to ensure our safety, we need to sacrifice some of our personal privacy.

The government’s right to spy seems to violate the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizures, and also to constitute a general threat to liberty. However, in a society plagued by terrorist threats and acts, it can seem reasonable for the government to acquire whatever information it can to make society safer.

But with so much of our personal information and conversation now accessible because of its digitization, and with computer technology able to review all of that information, it seems that there is little left unexposed to the government’s eye. One possible solution is to reject communication technology (no smartphones, no email, no wifi, no OnStar equipped vehicles, etc.), but who is prepared to do that? And doing so wouldn’t change the principle that’s at stake here: we’re being held suspect, until . . . well, we’re all just being held suspect.

How is our society to balance personal liberty and personal privacy? Can we feel at liberty to full self-expression while knowing that our privacy is breached? If the government’s position is to watch for possible illegal actions, and particularly, threats of violence, rather than to monitor all communicated thoughts and actions, then what have the innocent to lose? And what happens if we begin to err on the side of privacy and another 911 attack, or one worse, happens? Such questions admit no easy answers.

Pro-government surveillance:

- National Security Agency/Central Security Service (NSA)

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)

- Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)

Anti-surveillance groups:

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(7) Government controlled economics vs. Free market economics

Some economists (called “Keynesians”) believe that free markets are inherently unstable, prone to booms (bubbles) and busts (recessions, depressions)—also known as the “business cycle.” Therefore, free markets need to be controlled by the government in the form of fiscal policy (taxing, borrowing, and spending) and monetary policy (printing money and setting the interest rate), in order to smooth out the business cycle and prevent painful recessions.

Other economists (called “Austrians”) believe that government interference in the economy is what causes the business cycle in the first place, by causing savings (investment) to be misallocated in ventures that do not answer real demand and so are not sustainable over the long term. According to this theory, a healthy economy—one with maximum long-term growth and a minimum business cycle—may best be achieved by minimizing government interference with the free market.

Government should steer and control the economy:

- Levy Economics Institute (Bard College)

- Economic Policy Institute

- Paul Krugman’s blog and homepage

- Jared Bernstein’s blog

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

- Securities and Exchange Commission

- The Federal Reserve

The government should, as much as possible, keep its hands off the free market:

- The Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Cafe Hayek

- Library of Economics and Liberty (Liberty Fund initiative)

- Tom G. Palmer’s blog

- Peter Schiff’s blog

- Mercatus Center (at George Mason University)

- Universidad Francisco Marroquin

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(8) Global warming as real problem vs. Global warming as alarmism

The debate over global warming is highly complex, combining questions of fact and evidence (what do we actually know about the Earth’s changing temperature patterns) with question of morality and public policy (what is right and wrong and what should we do about it). It helps to separate out four issues:

(i) Is global warming real?

The issues here are strictly scientific, but that does not mean they are straightforward. The trouble is that not all sciences are equally reliable. The science here involves fluid dynamics (the earth’s atmosphere is a “fluid” in scientific parlance), which is a phenomenon tolerably well understood, but which is nevertheless subject to great uncertainties due to chaos (extreme sensitivity to very small influences). The inherently chaotic nature of the atmosphere means that there are severe limits to our ability to ever predict the weather (short-term atmospheric change in a specific geographical location) more than a few days out. The climate (long-term atmospheric change over larger regions) is more predictable in a very coarse-grained way (we know for sure that January in Chicago will be colder than July). However, the science relating to global warming attempts to make fine-grained predictions concerning changes in the overall pattern of climate—which is more like predicting the weather. None of this means that the claims about global warming are wrong; it does mean they ought to be treated with skepticism.

Still, when all is said and done, a modest warming trend over the course of the past century, while not steady (it seems to have stalled recently), nevertheless does appear to be moderately well supported by the available evidence. Which leads us to the next question:

(ii) If global warming is real, is it caused mainly by human activity?

Even if the predictions of global warming turn out to be correct, another purely scientific question still remains: Why it is happening? We know that the earth’s climate has fluctuated between warmer and colder periods many times in the recent and distant past. For example, it was warmer during the Middle Ages than it was during the 17th and 18th centuries (the “Little Ice Age”). It was much warmer when the dinosaurs were living than it is today. Clearly, these changes in climate had nothing to do with human activity. On the other hand, it is beyond dispute that CO2 levels have also increased recently, and it is certainly tempting to assume that this is the cause of the recent modest global warming (due to the “greenhouse effect”). It is tempting, but it is not certain. Some scientists believe that the rise in CO2 is caused by the warming trend, not the other way around. Still, assuming the CO2 increases are anthropogenic (caused by human activity) and are driving the warming, there is still the question: So what?

(iii) If global warming is real, how harmful is it likely to be?

This is where the climate change debate begins to get really heated (no pun intended), for two reasons: (a) the science begins to get even more inconclusive; and (b) moral considerations begin to enter in a major way—and of course people disagree even more about moral problems than they do about the status of scientific claims. The main question here is how, exactly, global warming will impact human life (and, for some, other species). Will the oceans really rise due to the melting of glaciers and ice caps? If so, by how much and how fast? No one can say for certain. Even if there is damage due to rising sea levels, will it be offset by higher crop yields (most crops do better in a warmer climate, and all plants benefit from higher CO2 levels). If both effects occur, how do we calculate the human costs against the benefits? These are real questions that ought not to be simply dismissed out of hand. However, neither should they be treated as though the answers were obvious, nor should anyone who raises them be treated as a criminal equivalent to a holocaust denier.

Assuming that global warming is real, is anthropogenic, and would on balance be a bad thing for humanity, there still remains this last question:

(iv) If global warming is real, caused mainly by human activity, and likely to be very harmful, what can we do about it?

The trouble here is that all of the proposed solutions have significant risks. If CO2 really is the main culprit, then reducing our CO2 emissions seems the obvious answer. But what does that mean? Does it mean a burst of new economic activity as we transition to green technology? Or does it mean dashing the dreams of hundreds of millions of people in the developing world who see rapid industrialization based on fossil fuels as their only hope for a better future? Might not moving the populations of coastal cities inland make more sense than de-industrialization? What about other approaches, such as seeding the oceans with genetically modified plankton to soak up CO2? But in that case, what about the risk of unforeseeable consequences from such massive manipulation of natural systems? Here, the scientific questions become well-nigh inseparable from the moral issues.

Finally, we must constantly keep in mind that politics drives the climate change debate at least as much as science. In general, it is safe to say that the most enthusiastic supporters of the mainstream position on climate change—that we must take decisive action now to stop it or even to roll it back—are also friends of unlimited, or omnipotent, government (government with no constitutional limitations on what it may do). Their enthusiasm derives in no small part from the prospect that they and their friends will assume a much larger role in running things in the future. Needless to say, those who doubt that unlimited government is a good thing are likely also to be more skeptical of the need to take decisive action now to halt or reverse global warming.

Advocates for decisive action now to halt or reverse climate change:

- Environmental Defense Fund

- Earth Institute

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- Climate Science Watch

- Skeptical Science

Climate change skeptics:

- Heartland Institute

- Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change

- Bjorn Lomborg

- Freeman Dyson

- Science and Public Policy Institute (Lord Monckton)

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(9) The Evolution Debate

The evolution debate is highly complex, involving two separate sets of issues that are too often conflated: (a) The evidence for evolution itself, that is, the common descent of all or most present-day living things from one or a few original ancestors; and (b) the adequacy of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection to fully explain (a).

More than two sides exist to this cultural conflict; in fact, at least five different positions may be distinguished.

(1) Neo-Darwinism: Most mainstream biologists are proponents of neo-Darwinism, believing both that evolution has occurred (i.e., point a above) and that the theory of natural selection provides a fully adequate explanation of this fact, when augmented by our modern understanding of population genetics and molecular biology (i.e., point b above). This position usually involves the further beliefs that (c) living things are essentially machines, and (d) living machines have been assembled step by step through a process of random variation of their parts (via genetic mutation) and the selective retention of the resulting novel machines that just happen to survive better than others. Advocates of this position include:

- National Center for Science Education

- Panda’s Thumb Blog

- The Richard Dawkins Foundation

- Why Evolution is True Blog

- Digital Evolution Lab

(2) Self-organizational theory: Advocates of this position accept (a), but reject (b). That is, they accept that evolution has occurred, but maintain that the theory of natural selection is inadequate to explain this fact. They also usually reject (c) and (d), maintaining that living systems are not really analogous to machines, and that new adaptive forms do not arise in a wholly random manner. Rather, living systems are conceived of by them as constituting a separate “living state of matter,” with its own sui generis dynamical laws, which permit evolution to occur in a quasi-intelligent, non-random manner. Advocates of this position include:

- James A. Shapiro (cf. his “natural genetic engineering”)

- G. Albrecht-Buehler’s Cell Intelligence Website

- Gerald H. Pollack Laboratory

- Information and Autonomous Systems Group (University of the Basque Country)

- Ezequiel di Paolo’s Evolutionary Robotics Group

- Alexei Kurakin

- Institute for Complex Adaptive Matter

(3) Theistic evolution: Advocates of this position accept the two main claims of neo-Darwinism: (a) and (b). Yet they typically cast a jaundiced eye at (c) and (d), regarding organisms as more than machines, but doing so on metaphysical rather than scientific grounds. At the same time, they say that evolution by natural selection is the result of God’s creative action in the world. Whether the randomness at the heart of the Darwinian conception of evolution can be reconciled with God’s direction of the course of evolution, or with special providence more generally, is a point of controversy within this school of thought. Advocates of this position include:

- BioLogos Foundation

- Faraday Institute (Cambridge University)

- Thank God for Evolution

- Metanexus

- Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences

(4) Intelligent design: Advocates of this position may or may not accept that evolution (as in point a) has occurred. The distinguishing characteristic of this position is its rejection of the theory of natural selection (point b), together with the claim that teleology or design is empirically detectable in all living things and justifies an inference to the existence of a designing intelligence (though without further specification as to who or what that intelligence might be—everything from a full-blown transcendent deity to teleological processes embedded in nature are logical possibilities for intelligent design). Design theorists thus agree with self-organization theorists in rejecting the all-sufficiency of natural selection by random variation ((b) and (d)), though design theorists tend to go further than self-organizational theorists in rejecting the creative potential of natural selection.

Because design-theoretic research often focuses on the machine-like features of organisms (e.g., molecular machines inside cells), intelligent design is often charged with taking the same reductive, mechanistic view of life as neo-Darwinism (point c), but this charge is mistaken: in admitting that life exhibits machine-like features, design theorists are far from conceding that living things are themselves machines. To conflate the two is to commit a parts-wholes fallacy. Advocates of the intelligent design position include:

- Discovery Institute’s Center for Science & Culture

- Bio-Complexity

- Evolutionary Informatics Lab

- Evolution News & Views

- Access Research Network

(5) Creationism: The last position in the evolution debate rejects the evidence that evolution has occurred (point a), and thus rejects any proposed mechanisms, natural selection or otherwise, by which evolution might have occurred. Points (b), (c), and (d) thus go by the board as well. Creationists hold that God created living things directly, without the mediation of evolution or any other natural or lawlike process. Many advocates of this position would further qualify as “young-earth creationists,” who read the first chapters of Genesis literally, as a scientific text, taking the earth and universe to be only a few thousand years old. Though overwhelmingly rejected in the mainstream academy, young-earth creationism has widespread support among the American public. Advocates of this position include:

- Institute for Creation Research

- Answers in Genesis

- Creation Museum

- Creation Research Society

- Creation Ministries International

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(10) Legalization of marijuana vs. Keeping marijuana illegal

The conflict over the legalization of marijuana occurs in two popular contexts: 1) in the debate whether marijuana is a legitimate medicine to alleviate certain ailments; 2) in the debate whether people should have the same freedom to consume marijuana as they do alcohol and nicotine. A third group, less frequently considered, advocates the use of marijuana for spiritual/religious reasons.

Those who want to see marijuana legal essentially believe that what should be a personal choice is, for whatever reason, being denied them. In other words, they see their personal liberty as being infringed upon.

On the other hand, those for keeping marijuana illegal may question its medicinal use but regard its recreational use as both harmful to the individual and not in society’s best interest. They claim that chronic usage undermines physical and psychological health, and that even regardless of personal health, legalization for recreational purposes could burden the insurance system and lead to an undesirable hedonistic mentality. The White House also claims that legalization will drop prices, thus putting the drug in more peoples’ hands.

For reformation of marijuana laws:

For medicalization:

Opposition:

- The White House (marijuana facts sheet)

- Citizens Against Legalizing Marijuana

- The American Society of Addiction Medicine

According to a recent Gallup poll,

58 percent of people polled favor legalization, and 26 states have

decriminalized or at least allowed marijuana for medical usage.

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(11) Anti-capital punishment vs. Pro-capital punishment

Who has the right to take a life, even if the life in question is that of a heinous criminal? And, if permission is granted to execute criminals, on what grounds? These are the typical questions associated with the capital punishment debate. However, there is much more to think about here, even at the risk of sounding as though the sanctity of life is not the main issue. Anti-capital punishment groups demand evidence showing that capital punishment deters other potential offenders, that executions are more economical than lifetime imprisonment, that the number of innocent victims is nil or virtually so, and that guidelines for who could be executed would not target certain demographics, namely ethnic minorities, the mentally ill, and those unable to afford the best council.

Pro-capital punishment groups tend to see justice in such cases as retribution. Even if executions are no more economical than lifetime imprisonment, that’s not the point. It’s the principle that matters, and that principle is echoed in many common mantras: eye for an eye, reap what you sow, what comes around goes around, etc. Pro-capital punishment groups also tend to believe that executions do in fact dissuade potential criminals, and that executions provides a sense of justice for survivors of the criminal’s doing.

Anti-capital punishment:

- National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

- Amnesty International USA

- Equal Justice USA

- Witness to Innocence

Pro-capital punishment:

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list

(12) Expanded view of marriage vs. Traditional marriage

One side in this debate views marriage as an essential feature of human nature, and as the foundation of human society. The institution of marriage clearly exists (whether through evolution or through God’s design) for a purpose: the procreation of the human race. This intrinsic purpose is written on the human body itself in the form of the complementarity of male and female sexuality. Marriage is thus viewed as not fundamentally about affection or personal fulfillment; it is about carrying out in a responsible manner a biological function that is necessary for the future of society and ultimately of the human species. While forms of marriage have varied from time to time in human history and from culture to culture, research suggests that in our type of society a traditional, two-parent family structure is, on balance, the best environment for providing children with social and psychological stability. While alternative or non-traditional families may be unavoidable in some circumstances, they fall short of this ideal, and for that reason ought not to be promoted by society as equivalent to traditional marriage.

The other side in this debate either denies that human nature has any essential characteristics—claiming that human beings are infinitely malleable—or else claims that biology is irrelevant to the issues of marriage, procreation, and the successful raising of children. They believe that traditional family structures are merely the result of men’s unequal physical power, which has resulted in male domination of women, and not of the biological complementarity of the sexes. In any case, they believe that marriage as a social institution has nothing inherently to do with procreation, but rather ought to be understood primarily as a symbolic statement of society’s support for diversity, inclusivity, and equality among all types of human beings who have mutual affection for one another. On this view, biology is simply irrelevant to the institution of marriage, and limiting marriage to traditional male/female couples is based on nothing more than bigotry, and so is inherently unjust.

Supporters of alternative forms of marriage:

Suporters of traditional marriage:

- Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family

- ITI – Master of Studies on Marriage and the Family

- Robert P. George blog

- Manhattan Declaration

Back to Key Cultural Conflicts list